Charles Frederick TUNNICLIFFE

Langley 1901 - Anglesey 1979

Biography

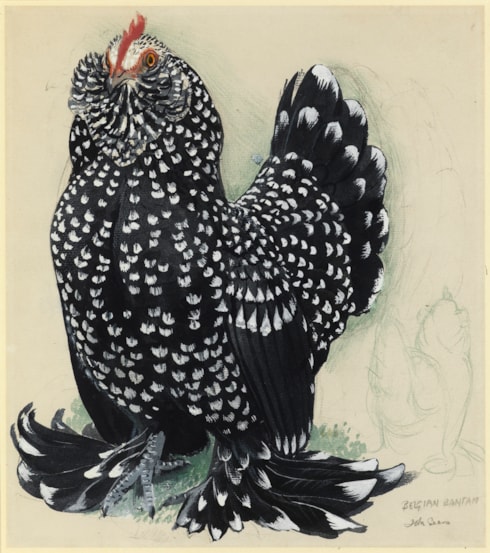

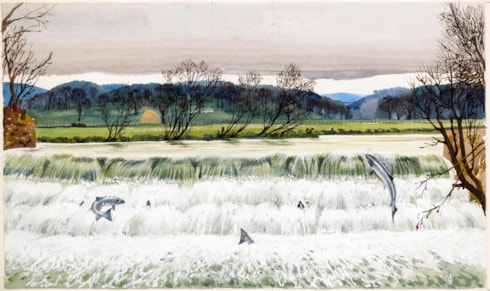

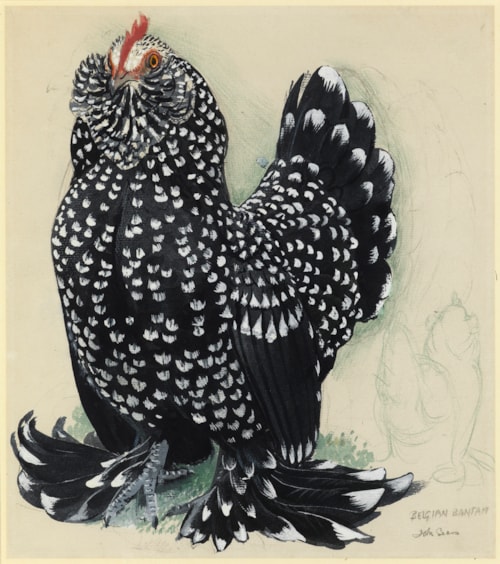

Born in a village near Macclesfield in Cheshire, Charles Tunnicliffe was raised on a small farm. He drew avidly from an early age and studied at the Macclesfield School of Art before winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London. He supported his scholarship with income earned from selling his etchings, which so impressed his tutors at the Royal College that he was allowed an extra year to work on this aspect of his art. After his graduation Tunnicliffe worked mainly as a commercial wood-engraver, producing designs for advertising images. In 1932 he was commissioned to produce wood engravings for an illustrated edition of Henry Williamson’s acclaimed novel Tarka the Otter. The success of Tunnicliffe’s illustrations for Tarka the Otter led to considerable demand for his work as an illustrator, and it is for this that he is perhaps best known today. He was also highly regarded for his depictions of birds, which he began to study in the 1930’s, and he eventually published several books of his bird illustrations. He also produced designs for other projects, such as calendars, advertisements and Brooke Bond tea cards. In 1944 Tunnicliffe was admitted as an Associate member of the Royal Academy, rising to Academician ten years later. From 1947 until his death in 1979 he lived and worked on the island of Anglesey in North Wales. A large group of drawings by Tunnicliffe are today in Anglesey, acquired en bloc from the artist’s studio by the Anglesey Borough Council at the urging of Kyffin Williams, the president of the Royal Cambrian Academy.

As Tunnicliffe’s close friend and fellow artist Kyffin Williams has written of him, ‘The whole of nature absorbed him and he was more sensitive to it than any man I have ever met; but it was nature in the particular that motivated his probing eye and forced him to live a life of obsession that produced a body of work that has hardly been equalled by any British artist...He had always been a good draughtsman, but never a facile one, for nothing had come easily to him, and what he had achieved in his middle years and in his later life was due entirely to the efforts of youth and early manhood. He had learned to master the art of the watercolour, the transparency of the wash and the subtle addition of gouache...He had filled his sketch books with information, both artistic and scientific, that will always be referred to by those who study our wild-life.’