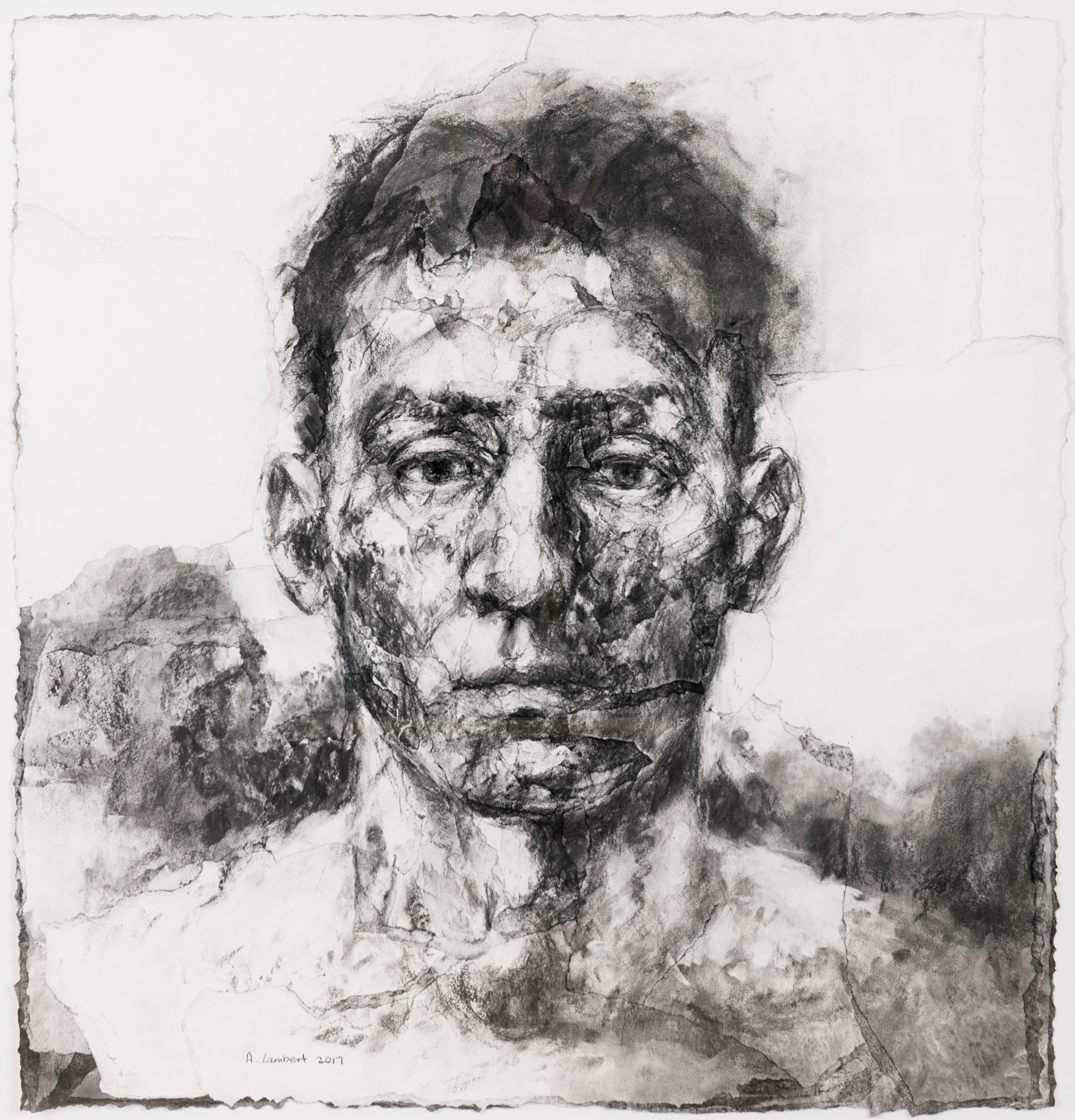

Alison LAMBERT

( 1957)

Vibius

Sold

Charcoal and pastel on paper.

Signed and dated A. Lambert 2017 in charcoal at the lower left.

841 x 795 mm. (33 1/8 x 31 1/4 in.)

Signed and dated A. Lambert 2017 in charcoal at the lower left.

841 x 795 mm. (33 1/8 x 31 1/4 in.)

Despite their initial appearance as realistic portraits, Alison Lambert’s highly expressionistic drawings of heads are not actual likenesses of specific people or studies from life. Instead they are the product of the artist’s imagination, based on an amalgamation of source material collected by her. mainly photographs of heads from books, magazines and newspapers. Sometimes the drawings are given classical, Biblical or mythological names, the better to establish them as archetypes. (The title given to the present sheet, Vibius, is a Latin male first name dating from ancient Roman times, though it was never a very common name. It was also the surname of a plebeian family of ancient Rome.) Lambert's drawings reflect her belief in capturing emotional states through a rendering of facial features. As the artist herself has stated, ‘I always have in mind a particular kind of emotion, like a raw truth, and it is this that I’m trying to bring out in my drawings of the head and face. The features of the head – who the person might be or whether they are male or female – doesn’t seem to be important. What is important is that I try to pull out of this person, in the strongest possible way, a raw expression of emotion or a distinct feeling. When this has been done to my satisfaction the drawing is finished.’

In a 2011 interview, Lambert described her working process: ‘I start each piece slightly differently but it is always on a plain sheet of paper. Usually I sprinkle charcoal on to the paper then, using my hands and a brush, I begin to describe a form. I then continue with a piece of charcoal and an eraser until the form becomes more evident. I continue to draw, rub out areas and change things around. If an area needs fresh white again due to too much rubbing out or the need to introduce light, I attach fresh pieces of white paper and continue to draw over the top and so on. Sometimes certain areas of a drawing can be many layers thick…I use thick willow charcoal, black pastel, tablet erasers from the Tate shop, soft brushes and a cobblers knife which has been adapted for me.’

The potency of Lambert’s drawn images is further made manifest by her intensely physical and almost violent working method. The artist tears away, scratches, scrapes and collages the layered surfaces of her drawings, while at the same time rubbing out and redrawing the forms over and over again in charcoal. This visceral technique has been a particular hallmark of the artist’s draughtsmanship from the beginning of her career. As one scholar has written, ‘In spite of the many changes her work has undergone, Lambert’s drawings have always been instantly recognisable for their remarkable physical characteristics; their deeply eroded and scraped surfaces; and their intense graphic qualities arising from her highly personal use of charcoal and black pastel. It is through her unique method of working – repeatedly drawing and erasing, tearing and gouging – that she has tried to delve beneath the skin of her subjects, to expose and lay bare the subjective condition of her characters and to explore the expressive possibilities of the human body and face.’

The sheer scale of these drawings, and the constant addition and subtraction of both paper and charcoal, resulting in a thickly layered surface, means that these immense works on paper are more constructed than simply drawn. As Peter McCarthy has pointed out, ‘Lambert intends these drawings to be seen in public or domestic interiors where their large scale might be experienced close to. Viewed at arm’s length, which is the artist’s habitual viewpoint, the imagery separates into its constituent parts. The chief experience at that distance is of unremitting tactility…The effort required in realising a fully worked image in this particular graphic idiom is considerable. It is not surprising therefore that she has gravitated towards a gestural, expressionistic style in which the combination of deliberate and accidental marks allows the steady build-up of both surface and image.’

Lambert has only ever worked as a draughtsman, and never as a painter. However, as McCarthy has stated, ‘In her work, the act of drawing is radicalised and extended until it gains the status of a fully-fledged image-making process. It is also, ironically, a painterly process. There is an absence of line. The form is modelled as fully as it would be in a painting except that the medium is dry and the effect monochromatic. Tactility is also more pronounced than it would normally be in a traditional drawing. Paper and charcoal are combined and reworked until they form a crust that is as pitted and worn as any heavy impasto.’

As the Canadian novelist Esi Edugyan, who owns one of Lambert’s large-scale drawings of heads, has described these works, ‘Utterly complex and mysterious, their expressions are impossible to pin down in a single word, and reflect back a strange and always changing combination of emotions that depend entirely on the mood of the viewer...It is this impossibility of emotions that Lambert captures. You find yourself fumbling to figure out exactly what it is you’re seeing, even as on a deeper level you’re already responding to it.’

In a 2011 interview, Lambert described her working process: ‘I start each piece slightly differently but it is always on a plain sheet of paper. Usually I sprinkle charcoal on to the paper then, using my hands and a brush, I begin to describe a form. I then continue with a piece of charcoal and an eraser until the form becomes more evident. I continue to draw, rub out areas and change things around. If an area needs fresh white again due to too much rubbing out or the need to introduce light, I attach fresh pieces of white paper and continue to draw over the top and so on. Sometimes certain areas of a drawing can be many layers thick…I use thick willow charcoal, black pastel, tablet erasers from the Tate shop, soft brushes and a cobblers knife which has been adapted for me.’

The potency of Lambert’s drawn images is further made manifest by her intensely physical and almost violent working method. The artist tears away, scratches, scrapes and collages the layered surfaces of her drawings, while at the same time rubbing out and redrawing the forms over and over again in charcoal. This visceral technique has been a particular hallmark of the artist’s draughtsmanship from the beginning of her career. As one scholar has written, ‘In spite of the many changes her work has undergone, Lambert’s drawings have always been instantly recognisable for their remarkable physical characteristics; their deeply eroded and scraped surfaces; and their intense graphic qualities arising from her highly personal use of charcoal and black pastel. It is through her unique method of working – repeatedly drawing and erasing, tearing and gouging – that she has tried to delve beneath the skin of her subjects, to expose and lay bare the subjective condition of her characters and to explore the expressive possibilities of the human body and face.’

The sheer scale of these drawings, and the constant addition and subtraction of both paper and charcoal, resulting in a thickly layered surface, means that these immense works on paper are more constructed than simply drawn. As Peter McCarthy has pointed out, ‘Lambert intends these drawings to be seen in public or domestic interiors where their large scale might be experienced close to. Viewed at arm’s length, which is the artist’s habitual viewpoint, the imagery separates into its constituent parts. The chief experience at that distance is of unremitting tactility…The effort required in realising a fully worked image in this particular graphic idiom is considerable. It is not surprising therefore that she has gravitated towards a gestural, expressionistic style in which the combination of deliberate and accidental marks allows the steady build-up of both surface and image.’

Lambert has only ever worked as a draughtsman, and never as a painter. However, as McCarthy has stated, ‘In her work, the act of drawing is radicalised and extended until it gains the status of a fully-fledged image-making process. It is also, ironically, a painterly process. There is an absence of line. The form is modelled as fully as it would be in a painting except that the medium is dry and the effect monochromatic. Tactility is also more pronounced than it would normally be in a traditional drawing. Paper and charcoal are combined and reworked until they form a crust that is as pitted and worn as any heavy impasto.’

As the Canadian novelist Esi Edugyan, who owns one of Lambert’s large-scale drawings of heads, has described these works, ‘Utterly complex and mysterious, their expressions are impossible to pin down in a single word, and reflect back a strange and always changing combination of emotions that depend entirely on the mood of the viewer...It is this impossibility of emotions that Lambert captures. You find yourself fumbling to figure out exactly what it is you’re seeing, even as on a deeper level you’re already responding to it.’

Born in Kingston in Surrey, the British artist Alison Lambert studied at the Leek School of Art and Design at the University of Derby before earning a degree in Fine Art at Coventry Polytechnic between 1981 and 1984. After her graduation she moved into a large studio in the Canal Basin Warehouse complex in Coventry, where she still works today. Lambert had her first solo exhibition in 1988 and has since regularly shown her work in solo and group shows in London - mainly at the Jill George Gallery - and elsewhere. While her earliest drawings were rooted in pagan or mythic themes and featured human figures and horses, she eventually developed an interest in more classical forms. These in turn led to a series of monumental drawings of single figures, larger than life-size, which were begun around 2000 and garnered considerable critical attention when they were exhibited in 2005.

For the past two decades the artist has chosen to concentrate on a series of large-scale charcoal drawings of heads and faces. These compelling works - of which the present sheet, executed in 2017, is a fine example - are characterized by a visceral technique involving the repeated and vigorous application and eradication of charcoal, as well as the tearing and pasting of strips of paper to create densely layered images that, in the words of one writer, ‘inevitably cause us to reflect on their deeper meaning and their emotional force.’ The artist has also been active as a printmaker, establishing a print workshop in her studio around 2007 and producing monotypes and etchings. Drawings and prints by Lambert are today in the collections of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester and the Swindon Museum and Art Gallery, as well as the Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minnesota and the Art Gallery of Hamilton in Ontario.

Writing in 2005, the scholar Alan Dyer noted that, ‘During the course of her career Lambert’s drawings have provided two routes through which her ‘findings’ have been communicated. The first is the human figure which obsesses her and which she feels gets her nearer to her goal – that of unearthing a presence in the physical body; in the new work the subject is the head and the face, with its endless variety of expressive features. The second route is the physical medium she is using to carry out her interrogations; the fragmented surfaces and networks of expressive marks – metaphors not only for the internal states of her subjects but also for the emotional journey which she herself makes in excavating those states...In the new work she concentrates exclusively on portraiture, on the capacity of the human face to express or communicate intense emotion. The familiar scraped and torn surfaces of the drawings no longer strip away and undermine the identity of her subjects, they serve, rather, to intensify the emotional charge which is written into their facial features. It might be expected that the heavily eroded surfaces of the drawings would rob Lambert’s subjects of their identity and sense of humanity but this is not the case. The fragmented and ‘worried’ surfaces seem to accentuate the humanity of her subjects by giving them an even greater emotional intensity.’

For the past two decades the artist has chosen to concentrate on a series of large-scale charcoal drawings of heads and faces. These compelling works - of which the present sheet, executed in 2017, is a fine example - are characterized by a visceral technique involving the repeated and vigorous application and eradication of charcoal, as well as the tearing and pasting of strips of paper to create densely layered images that, in the words of one writer, ‘inevitably cause us to reflect on their deeper meaning and their emotional force.’ The artist has also been active as a printmaker, establishing a print workshop in her studio around 2007 and producing monotypes and etchings. Drawings and prints by Lambert are today in the collections of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester and the Swindon Museum and Art Gallery, as well as the Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minnesota and the Art Gallery of Hamilton in Ontario.

Writing in 2005, the scholar Alan Dyer noted that, ‘During the course of her career Lambert’s drawings have provided two routes through which her ‘findings’ have been communicated. The first is the human figure which obsesses her and which she feels gets her nearer to her goal – that of unearthing a presence in the physical body; in the new work the subject is the head and the face, with its endless variety of expressive features. The second route is the physical medium she is using to carry out her interrogations; the fragmented surfaces and networks of expressive marks – metaphors not only for the internal states of her subjects but also for the emotional journey which she herself makes in excavating those states...In the new work she concentrates exclusively on portraiture, on the capacity of the human face to express or communicate intense emotion. The familiar scraped and torn surfaces of the drawings no longer strip away and undermine the identity of her subjects, they serve, rather, to intensify the emotional charge which is written into their facial features. It might be expected that the heavily eroded surfaces of the drawings would rob Lambert’s subjects of their identity and sense of humanity but this is not the case. The fragmented and ‘worried’ surfaces seem to accentuate the humanity of her subjects by giving them an even greater emotional intensity.’

Provenance

Jill George Gallery, London.

Exhibition

London, Jill George Gallery at the Coningsby Gallery, Alison Lambert: New Charcoal Drawings and Monotypes, 2017.