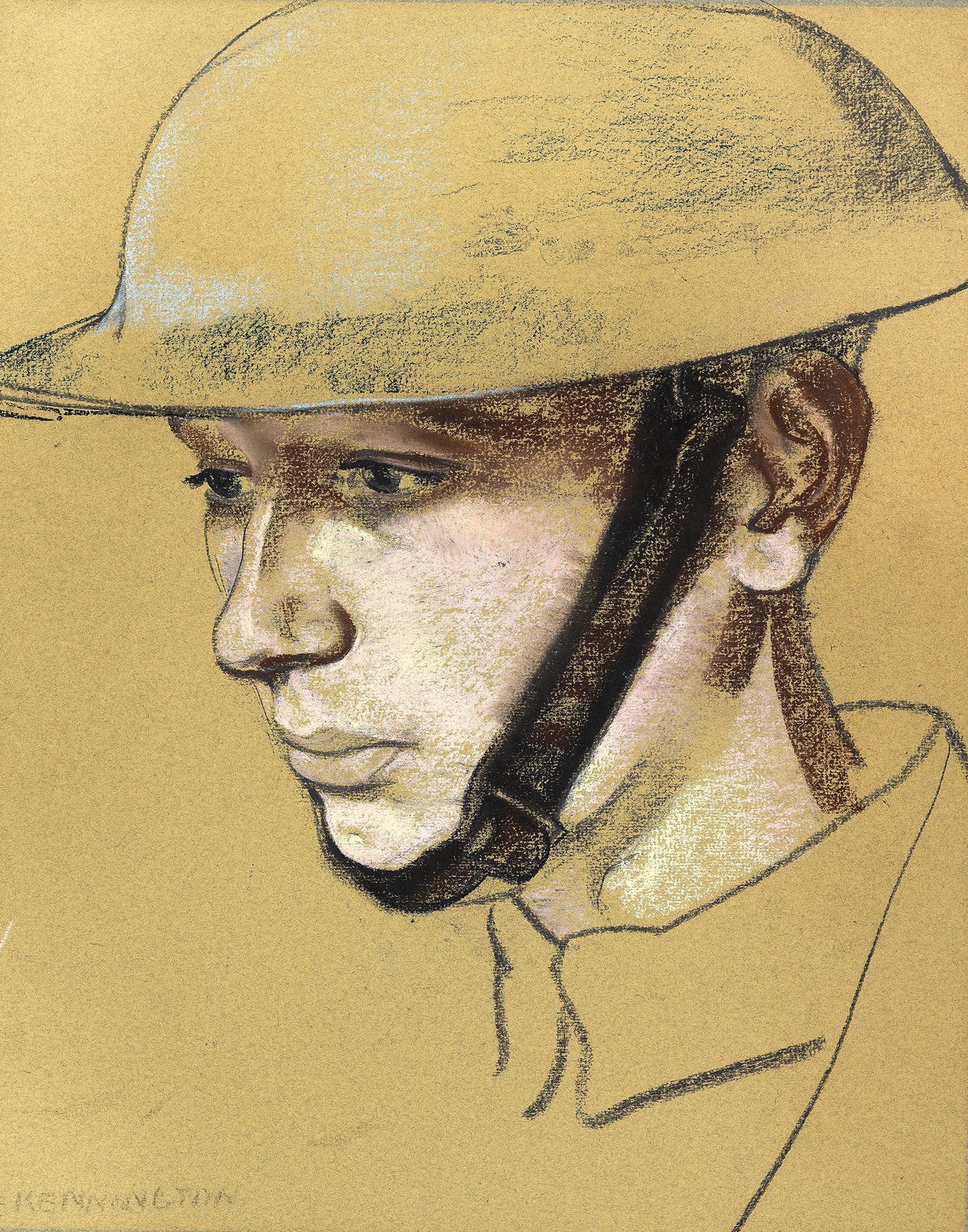

Eric KENNINGTON

(London 1888 - Reading 1960)

Portrait of a Soldier

Sold

Coloured chalks and charcoal on faded blue-grey paper.

Signed E. KENNINGTON at the lower left.

380 x 305 mm. (11 x 12 in.) [image]

467 x 381 mm. (18 3/8 x 15 in.) [sheet]

Signed E. KENNINGTON at the lower left.

380 x 305 mm. (11 x 12 in.) [image]

467 x 381 mm. (18 3/8 x 15 in.) [sheet]

In the preface to the catalogue of the exhibition of Eric Kennington’s war drawings, held at the Leicester Galleries in London in 1918, Robert Graves wrote of the artist that ‘he is a soldier, and at home in trench and shell hole, knows what is happening, what to see, where and how to see it; more important still, he has the trench point of view, and cannot forget how in the dark days of 1914 he gulped his rum and tea, fried his bacon, filled his sand-bag, ducked under his first bullet, stared into black night across the parapet and endured terror and misery as a private in the infantry. The British soldier, as Mr. Kennington has known and portrayed him, is a changeless type, wherever he fights, however he is armed, equipped, organised...in the middle of horror, frozen, stunned, bleeding, thirsty, tired nearly to death, choking with gas, the British soldier frowns and sweats and shows with what majesty he can fight.’

Similarly, in one of a series of books about Official War Artists, Campbell Dodgson wrote that, ‘The resolute, weather-beaten faces of soldiers, hardened by endurance, nerved to deeds of daring in the coming raid, or pathetically altered by suffering as they lie in hospital, gassed or blinded, unconscious or bearing acute pain with stoicism – these are Mr. Kennington’s principal themes. Many of his drawings are unspeakably sad; how could they be otherwise, being manly and serious portraits of men who act or suffer in this most terrible of wars?’ Kennington himself, in a letter of June 1918, noted of his drawings that he tried to ‘get as much as possible of the magnificence of the men, all their fine qualities and varied characters and appearances.’

The present sheet once belonged to Kennington’s friend, the war poet Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), who met the artist, through Robert Graves, in 1918. He later helped Kennington to find a new studio on the Brompton Road after his final return from the battlefields of France in 1919. Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, published in 1930, has been described as ‘probably the classic personal account of the First World War in English.’7 In a letter written in July 1918, probably after seeing the Leicester Galleries exhibition that summer, Sassoon stated that he thought that Kennington’s ‘soldier drawings [were] excellent.’

Similarly, in one of a series of books about Official War Artists, Campbell Dodgson wrote that, ‘The resolute, weather-beaten faces of soldiers, hardened by endurance, nerved to deeds of daring in the coming raid, or pathetically altered by suffering as they lie in hospital, gassed or blinded, unconscious or bearing acute pain with stoicism – these are Mr. Kennington’s principal themes. Many of his drawings are unspeakably sad; how could they be otherwise, being manly and serious portraits of men who act or suffer in this most terrible of wars?’ Kennington himself, in a letter of June 1918, noted of his drawings that he tried to ‘get as much as possible of the magnificence of the men, all their fine qualities and varied characters and appearances.’

The present sheet once belonged to Kennington’s friend, the war poet Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), who met the artist, through Robert Graves, in 1918. He later helped Kennington to find a new studio on the Brompton Road after his final return from the battlefields of France in 1919. Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, published in 1930, has been described as ‘probably the classic personal account of the First World War in English.’7 In a letter written in July 1918, probably after seeing the Leicester Galleries exhibition that summer, Sassoon stated that he thought that Kennington’s ‘soldier drawings [were] excellent.’

The son of a portrait and genre painter, Eric Henri Kennington studied at the Lambeth School of Art and at the City and Guilds School, and first came to public notice for his paintings of East End costermongers. With the outbreak of the First World War, Kennington immediately volunteered for duty, and served as a private in the ‘Kensingtons’; a battalion of part-time soldiers of the London Regiment. He served in France in the winter of 1914, eventually returning to England and receiving a medical discharge after being shot in the foot and losing a toe. His first significant war painting, The Kensingtons at Laventie: Winter 1914, was exhibited to much acclaim at the Goupil Gallery in the spring and summer of 1916. The painting brought Kennington to the attention of the artist William Rothenstein, who became a close friend and colleague. It was Rothenstein who campaigned for Kennington to be appointed an Official War Artist. As he described the younger artist to one correspondent: ‘No-one has so marked a gift as he for drawing and understanding the magnificence of the Tommy.’

On his own, Kennington made a return trip to the Somme in December 1916, and some thirty portrait drawings of British and French soldiers that he made during this journey were eventually shown at the Goupil Gallery in March 1917. Partly as a result of this exhibition, he was appointed an Official War Artist, and in August 1917 returned to the Western Front, with a specific brief to make drawings of British infantrymen, or ‘tommies’. As a former ‘tommy’ himself, he was able to produce convincing and realistic depictions of the soldiers he encountered; as the scholar and British Museum curator Campbell Dodgson noted, Kennington was ‘a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file.’ Commissioned to produce several drawn portraits during his time in France - as the artist wrote in a letter to an official at the Department of Information in London, ‘a portrait draughtsman is welcomed out here, everybody wanting to be drawn from Generals to Privates and, consequently, I am treated magnificently’ - he also produced landscapes of the trenches and their shattered surroundings. In December 1917 Rothenstein joined Kennington in France, and the two artists produced a number of portrait drawings of soldiers, which Rothenstein hoped might eventually be published as a book by the Ministry of Information, although the project never came to fruition.

Kennington eventually returned to England after more than seven months on the Western Front, and a selection of the work he had produced was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in the summer of 1918. The exhibition, entitled The British Soldier, was accompanied by a catalogue with an essay written by the poet Robert Graves. Later that year, however, Kennington resigned his commission as a War Artist, over a disgreement with the price offered by the government to acquire his work for the collection of the recently founded Imperial War Museum. Towards the end of the war Kennington was commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Scheme to accompany the soldiers of a Canadian infantry unit as it marched into a defeated Germany. Another highly successful exhibition of his war drawings was held at the Alpine Club Gallery in London in 1920.

Soon after his return to London Kennington moved into a new studio, and in the early 1920s began to take up stone carving, mentored by Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill; among his first public commissions as a sculptor was a memorial to the 24th Infantry Division in Battersea Park, completed in 1924. From this time onwards Kennington would describe himself as primarily a sculptor, though he continued to accept portrait commissions. Throughout the 1920s, art critics favourably compared Kennington’s skill as a portrait draughtsman to such contemporaries as William Orpen, Augustus John and John Singer Sargent. He contributed a number of portrait drawings as illustrations for an edition of T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, first published in 1922, and also gave lectures at the Royal College of Art (whose Principal was Rothenstein), while continuing to work as a sculptor. Among his notable public sculptures is an effigy of his friend Lawrence for a monument in St. Martin’s Church in Wareham in Dorset, on which he worked between 1937 and 1939 In 1939 Kennington was appointed an Official War Artist for the second time. He was attached to the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force between 1939 and 1942, and spent the later years of the war working for the War Office as a portraitist. Elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1951 and a full Academician eight years later, Kennington spent much of the last years of his career creating tomb monuments for Anglican churches.

Provenance

Siegfried Sassoon, London

Thence by descent

Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 6 June 2007, lot 105.