Edgar DEGAS

(Paris 1834 - Paris 1917)

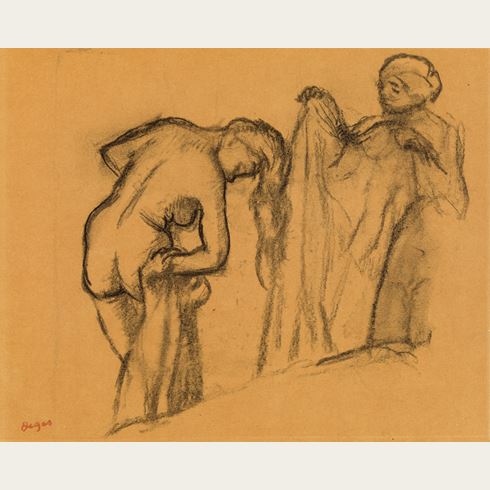

Deux danseuses en maillot (Deux danseuses nues en arabesque)

Stamped with the Degas vente stamp (Lugt 658) at the lower left.

Inscribed Degas no.11468 / Deux danseuses en maillot (dessin) on a label pasted onto the backing board.

Inscribed V.A.D. 3 / 195 on a label pasted onto the backing board.

Numbered x109 in blue chalk and 479 in red chalk on the backing board.

450 x 540 mm. (17 3/4 x 21 1/4 in.)

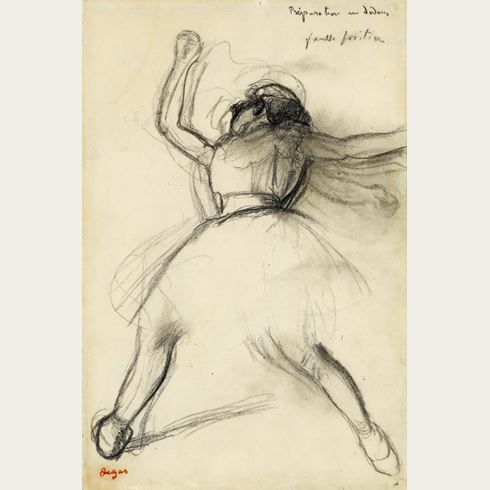

The ballet pose depicted in this drawing is part of an ‘arabesque penchée’, in which the dancer begins by standing erect and then slowly tilts her body forwards while raising and extending one leg behind her. This is the same movement captured in a series of three sculptures by Degas, modeled by the artist in wax between 1882 and 1895 and cast in bronze after his death, depicting a nude in three phases of the arabesque4. The pose of the two dancers in this drawing is very close to one of these sculptures, the Grand Arabesque, Second Time (Grande arabesque, deuxième temps), and Degas is likely to have used the wax model as the inspiration for the drawing.

This cross-fertilization between sculptures, drawings and paintings seems to have been a frequent occurrence in Degas’s studio between around 1890 and 1910; indeed, he may have regarded his sculptures primarily as studies for works in two dimensions.

Degas’s particular interest in the arabesque form is reflected in the fact that he produced a total of eight sculptures of dancers in various stages of this movement. As Alison Luchs has written, ‘Of all the movements of classical ballet, the arabesque seems to have held the greatest fascination for Degas as a sculptor...The arabesque is a moment of balance in which the dancer reaches a peak of tension between submitting to gravity and escape from it. Her body has one point of contact with the earth and endless directional possibilities for the other limbs that seem to strain for freedom...The difficulty for a model to maintain the relevant poses must also have stimulated [Degas] to explore the arabesque in sculpture. The resulting waxes provided a three-dimensional aid for studying this human movement for the treatments that appear repeatedly in Degas’ paintings and pastels from the 1870s through the 1890s.’

A closely related drawing of three nude dancers in the same arabesque pose was sold alongside the present sheet at the third Degas studio sale in 1919. In both drawings a curved line at the left of the composition recalls the prominent spiral staircase in the dance classroom of the Paris Opéra on the Rue Le Peletier. This spiral staircase is seen in a number of Degas’s dance rehearsal compositions of the 1870’s and 1880’s, in which a line of dancers are depicted in arabesque poses; these include a painting of a Dance Rehearsal (La répétition de danse) of c.1874 in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, and a large pastel drawing of a similar subject, in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. (It is interesting to see this reference to the Rue Le Peletier classrooms in Degas’s work well into the 1890’s and beyond, since the building itself was destroyed by fire in 1873.)

Also stylistically comparable is a large charcoal drawing of a single dancer in an identical pose, though seen from a more frontal position, in a private collection. DeVonyar and Kendall’s comments on the latter drawing may equally be applied to the present sheet: ‘The charcoal drawing Grand Arabesque, Second Time is exceptionally plausible in its suggestion of transience. Heavy contours around the lower leg and parts of the upper torso remind us of the sheer mass of the human body, while almost entirely erased marks elsewhere evoke our fleeting perceptions of figures and other objects seen in passing. Less anatomically precise than the drawings that Degas made in the 1870s and 1880s, this superb sheet nevertheless seems to describe his subject with immense authority, confronting us with the experience of being present when the living dancer was expertly posing.’

Like many of the charcoal and pastel drawings of the artist’s late career, the present large sheet is drawn on papier calque, or tracing paper. This type of paper had a smooth surface and, though thin, was strong enough to be rolled and unrolled repeatedly in the studio. As George Shackelford has noted, ‘In the 1890s…Degas turned to a new shortcut for transferring a successful idea from one surface to another. For this purpose, he used tracing paper – papier calque – through which he could see a drawing below. The smooth, uniform surface of the hard-milled paper provided an unusual but ideal foil for the charcoal sticks that he favored as drawing tools, allowing him both to obtain very smooth, continuous lines unbroken by the tooth of rougher papers and also to smudge and wipe the charcoal, or even to erase it, to create shadow or to correct a misplaced contour. Such tracings could stand on their own as independent sheets and were sometimes signed and sold by Degas, but the vast majority of them remained in the studio, to be discovered at the time of his death.’

Provenance

Literature