Auguste RODIN

(Paris 1840 - Meudon 1917)

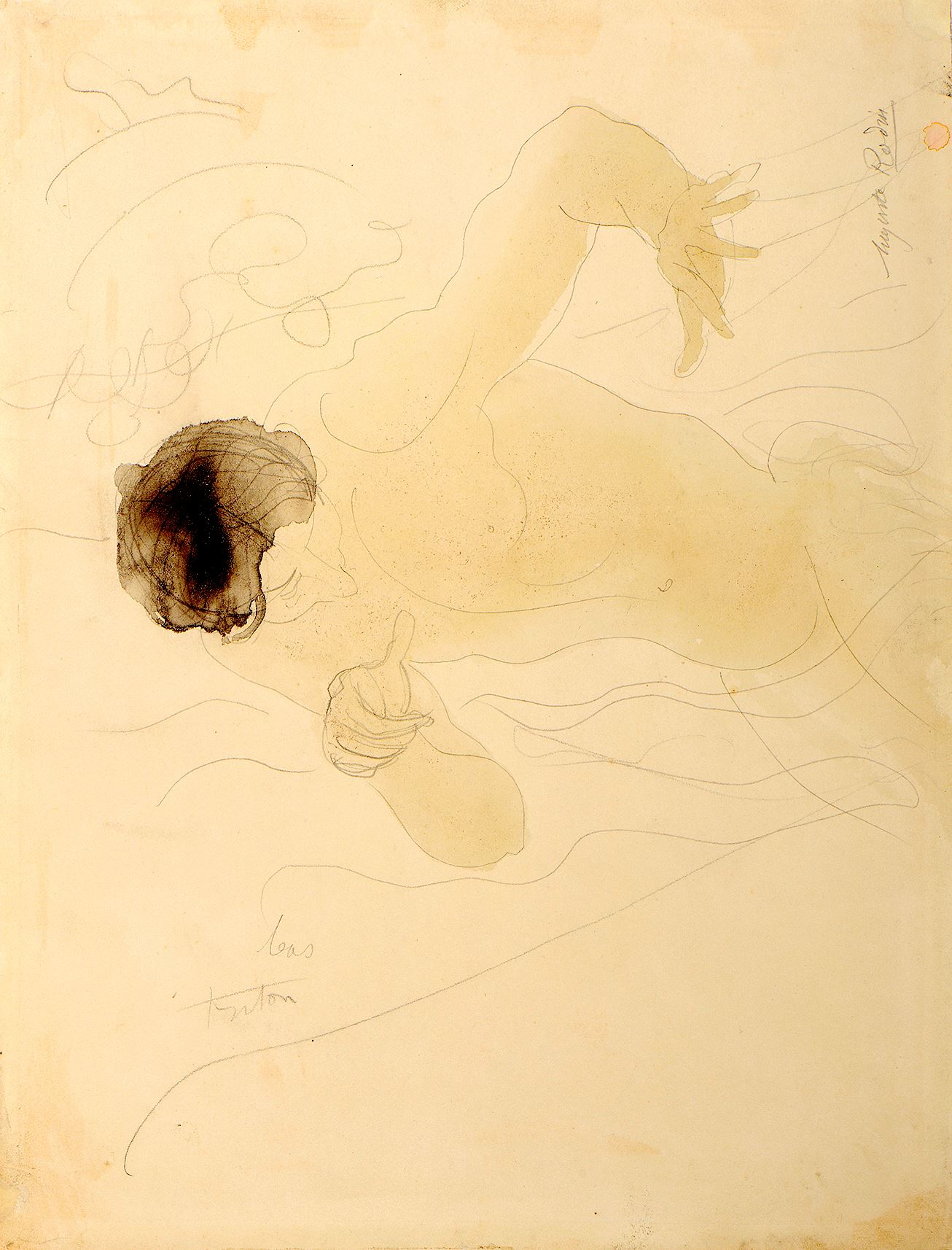

Triton

Sold

Pencil and watercolour.

Signed Auguste Rodin at the upper right.

Inscribed bas and triton near the lower left corner. 325 x 249 mm. (12 3/4 x 9 3/4 in.)

Signed Auguste Rodin at the upper right.

Inscribed bas and triton near the lower left corner. 325 x 249 mm. (12 3/4 x 9 3/4 in.)

Drawn around 1900, the present sheet may be added to a group of around a hundred drawings of male nudes, inspired by mythology or antiquity, produced by Auguste Rodin from the late 1890s onwards. These drawings are often titled by the artist with reference to such mythological figures as Homer, Ulysses, Icarus, Prometheus or Neptune; several examples are in the collection of the Musée Rodin in Paris. As the Rodin scholar Christina Buley-Uribe has noted of the present sheet, ‘Drawings of male nudes are not rare in Rodin’s work even though they are less numerous than the hundreds of drawings made after female models. The Ulysses series (Musée Rodin) and the drawing of Marsyas (private collection)...have shown, amongst other things, the reinterpretation made by Rodin from numerous drawings of male models, in light of ancient texts or inspired by Greco-Roman mythology. Triton is not an exception. Redrawn from a Half length study of a man (D. 463, Paris, musée Rodin) sketched ‘blindly’ as Rodin was used to doing, without looking at his sheet of paper, the drawing has been turned vertically in order to create a more dynamic figure. The movement of Triton, toppling to the left, is reinforced by the presence of a dolphin, summarily outlined, diving in the background in an opposite motion.’

As noted by Clément Janin in his 1903 article, Rodin would often take his initial pencil drawing and make a tracing from it, probably by holding it up to a window. More carefully drawn, this second version ‘stablizes the composition on the page, reduces the distortions and pentimenti, and arrives at a more unified visual image.’ Such is the case with the present sheet which, as Buley-Uribe points out, is traced from a drawing of the same figure, rapidly drawn in pencil alone, in the collection of the Musée Rodin. With this second, more refined treatment of the composition, Rodin added pale washes of watercolour to the figure, and added a title to the work. A somewhat similar pose and treatment of the nude male figure is seen in a drawing of a Kneeling Male Nude with One Hand on the Ground in the Musée Rodin, which, like the present sheet, was in turn based on a rough pencil drawing, also in the Musée Rodin. It remains uncertain which orientation Rodin intended this drawing to be viewed. Although the sheet is signed as if the composition was meant to be seen horizontally, as is the case with the cognate drawing in the Musée Rodin, the artist also titled the work and added the word ‘bas’ (’bottom’) in such a way as to imply that this more elaborate version of the composition should be viewed vertically. As has been noted of Rodin’s late drawings, the artist ‘sometimes altered the center of gravity of his figures by turning the sheet on edge and writing the word “bas” below the new and perhaps even more interesting position, changing, say, a reclining figure into a flying or hovering one.’ Rodin’s late watercolours are among his most personal and expressive works, and distill a lifetime of study of the human body into the simplest and most immediate terms.

As noted by Clément Janin in his 1903 article, Rodin would often take his initial pencil drawing and make a tracing from it, probably by holding it up to a window. More carefully drawn, this second version ‘stablizes the composition on the page, reduces the distortions and pentimenti, and arrives at a more unified visual image.’ Such is the case with the present sheet which, as Buley-Uribe points out, is traced from a drawing of the same figure, rapidly drawn in pencil alone, in the collection of the Musée Rodin. With this second, more refined treatment of the composition, Rodin added pale washes of watercolour to the figure, and added a title to the work. A somewhat similar pose and treatment of the nude male figure is seen in a drawing of a Kneeling Male Nude with One Hand on the Ground in the Musée Rodin, which, like the present sheet, was in turn based on a rough pencil drawing, also in the Musée Rodin. It remains uncertain which orientation Rodin intended this drawing to be viewed. Although the sheet is signed as if the composition was meant to be seen horizontally, as is the case with the cognate drawing in the Musée Rodin, the artist also titled the work and added the word ‘bas’ (’bottom’) in such a way as to imply that this more elaborate version of the composition should be viewed vertically. As has been noted of Rodin’s late drawings, the artist ‘sometimes altered the center of gravity of his figures by turning the sheet on edge and writing the word “bas” below the new and perhaps even more interesting position, changing, say, a reclining figure into a flying or hovering one.’ Rodin’s late watercolours are among his most personal and expressive works, and distill a lifetime of study of the human body into the simplest and most immediate terms.

Auguste Rodin’s immense success and reputation as a sculptor has tended to somewhat overshadow appreciation of his skills as a draughtsman. Yet throughout his career he laid great emphasis on his drawings, and wanted them to be better known. He hung countless drawings in his studio at the Hôtel Biron, and sold or gave away many sheets as gifts. From the 1880’s onwards, he mounted several exhibitions of his drawings, culminating in the inclusion of hundreds of studies as part of the great retrospective exhibition of his work held on the Place de l’Alma in Paris during the Exposition Universelle of 1900. At his death, Rodin left a massive group of some eight thousand drawings, the vast majority of which are today in the collection of the Musée Rodin in Paris. Yet while he drew extensively throughout his career, he left almost no dated drawings, and only rarely can a drawing be related to a specific sculpture. As such it is difficult to accurately date his drawings; all the more so because he often reworked his drawings several times, over a period of several years after he had first made them.

Around 1890 Rodin became very busy with sculptural commissions, notably the Monument to Balzac, which occupied him between 1891 and 1898. It had been thought by some early scholars that, burdened with work, the artist drew very little in the final decade of the 19th century. This has, however, been proved to be incorrect and, if anything, his intense engagement with the process of developing his ideas for the Balzac sculpture stimulated his approach to drawing. Rodin’s manner of drawing began to change in the late 1890’s, becoming somewhat looser and more expressive, with a greater use of watercolour applied in diaphanous washes. He often made drawings from the model without looking at the sheet of paper in front of him; this may have also been the result of his habit of allowing his models to walk freely around his studio, capturing their movements with his pencil in a kind of graphic shorthand.

In 1903, the writer Clément Janin provided a fascinating description of Rodin’s method of drawing at this late stage in his career: ‘In his recent drawings, Rodin uses nothing more than a contour heightened with a wash. Here is how he goes about it. Equipped with a sheet of ordinary paper posed on a board, and with a lead pencil – sometimes a pen – he has his model take an essentially unstable pose, then he draws spiritedly, without taking his eyes off the model. The hand goes where it will: often the pencil falls off the page...The master has not looked at it once. In less than a minute, this snapshot of movement is caught. It contains, naturally, some excessive deformations, unforseen swellings, but, if the relation of proportions is destroyed, on the other hand, each section has its contours and the cursive, schematic indication at its modelling...The first effort completed, Rodin takes up the work again, sometimes corrects it directly with a stroke of red pencil; but most often, it is in tracing that he rectifies it. His great preoccupation at this time is to conserve and even to amplify the impression of life that he has obtained from the direct sketch...The tone that he adds, this wash of Sienna that goes over the limits of the line, seems capricious or negligent, and has, in reality, the effect of thickening this enlargement, as well as binding together the contours.’

Many of these late drawings were shown in public for the first time, albeit uncatalogued, at the exhibition of his sculptures mounted by Rodin in a private pavilion on the Place de l’Alma in Paris during the Exposition Universelle of 1900. Other drawings of this type were shown elsewhere in Europe in the early years of the century. When some of Rodin’s late watercolours of nudes were exhibited in Rome in 1902, the young Swiss artist Paul Klee was profoundly struck by them. As Klee wrote in his diary, ‘Rodin – with caricatures of nudes – caricatures! – a species previously unknown in his case. And he’s the best I’ve ever seen at it, astonishingly brilliant. Contours drawn with a few scant strokes of the pencil, flesh tones added with a full brush in watercolor, and sometimes drapery suggested with another color, greenish, say. That’s all, and the effect is simply monumental.’

Provenance

Anonymous sale, Marseille, Leclere, 8 March 2008, lot 132

Private collection.

Literature

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the drawings and paintings of Rodin, currently in preparation by Christina Buley-Uribe.