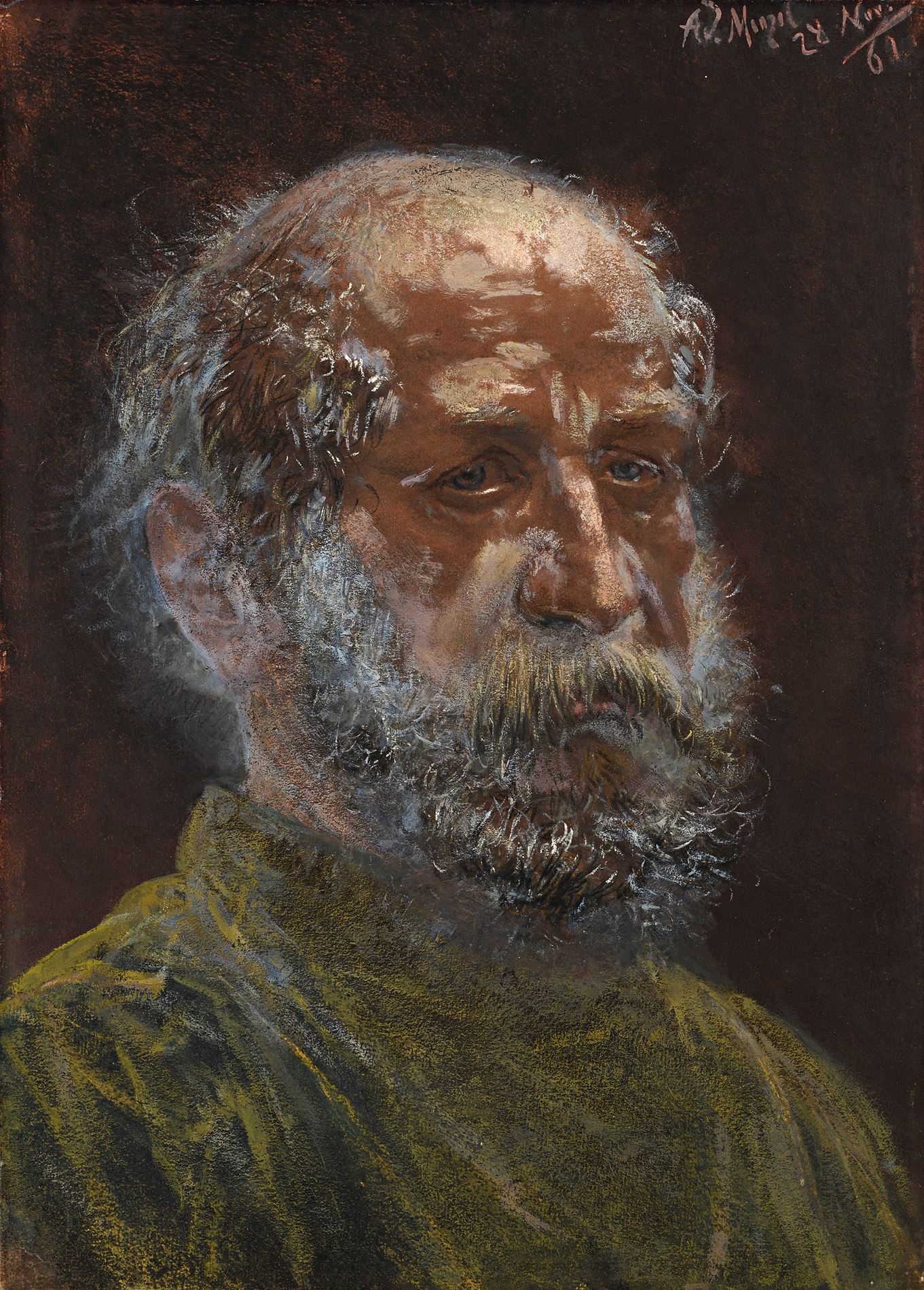

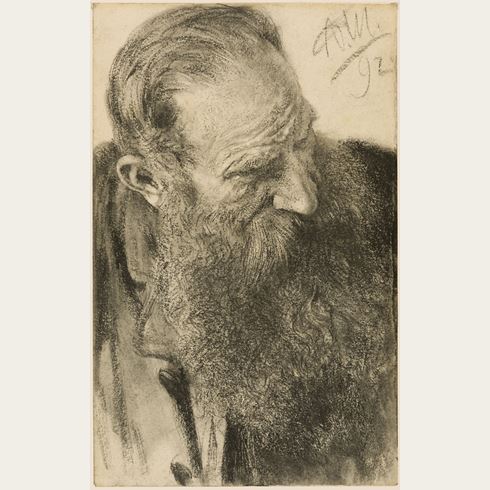

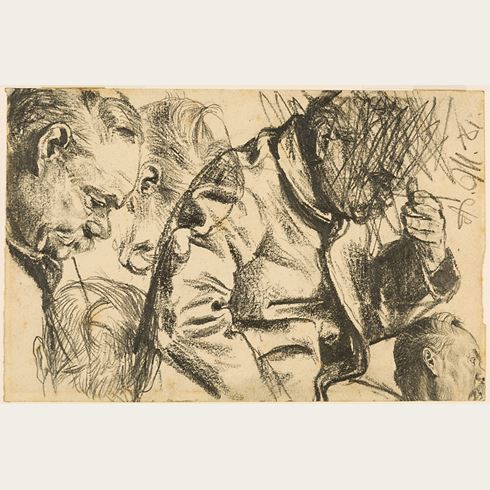

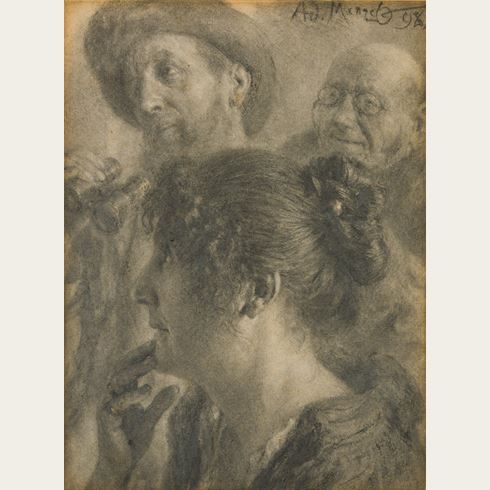

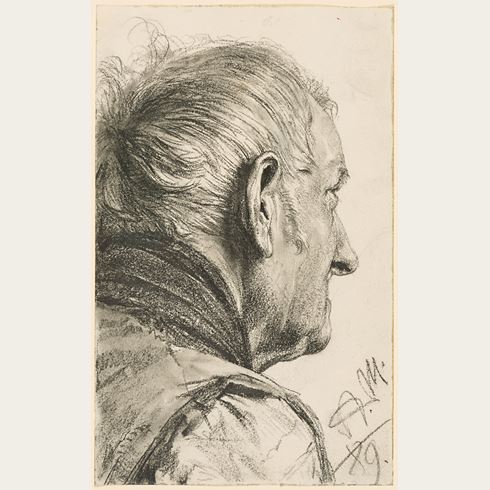

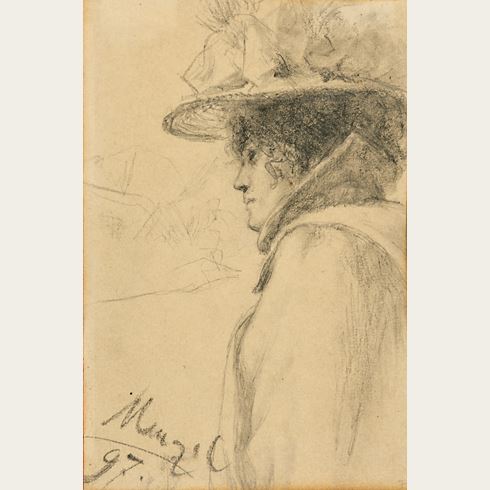

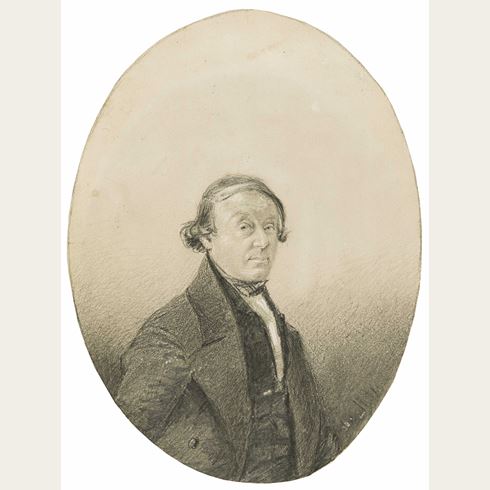

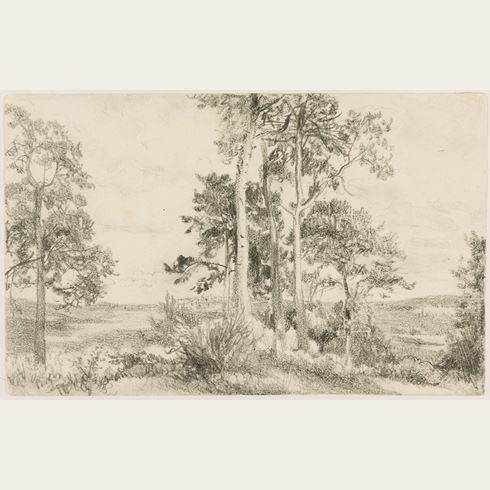

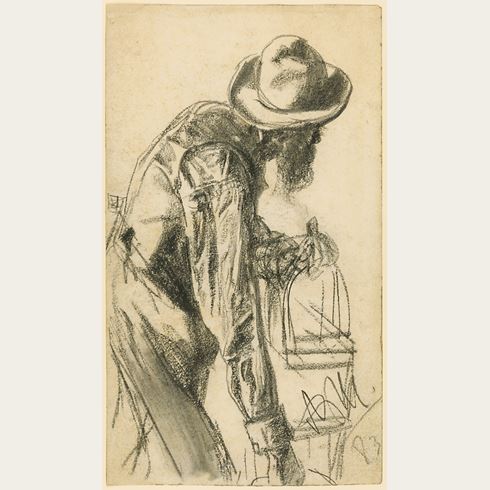

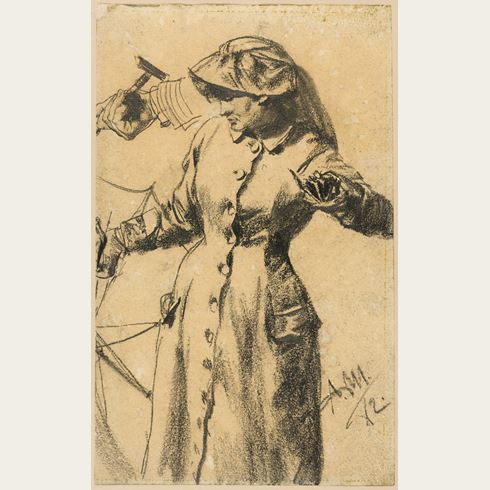

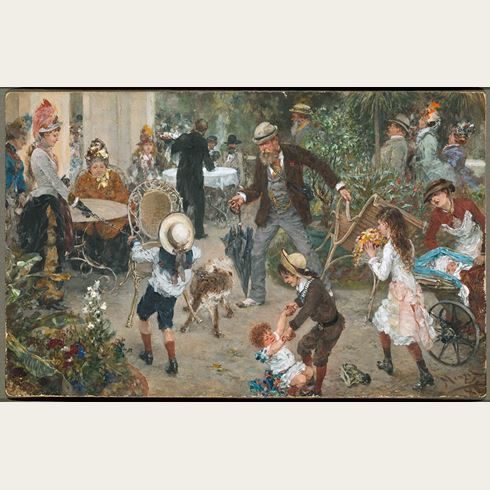

Adolph MENZEL

(Breslau 1815 - Berlin 1905)

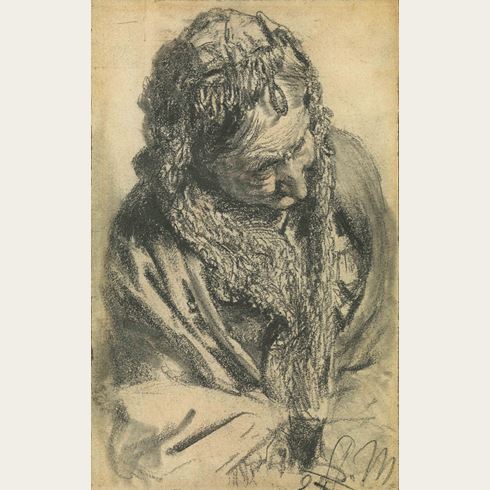

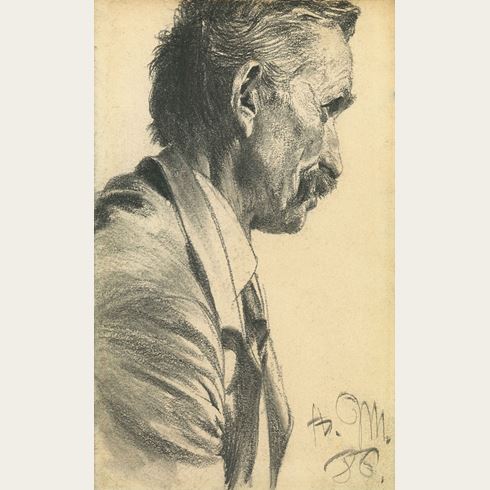

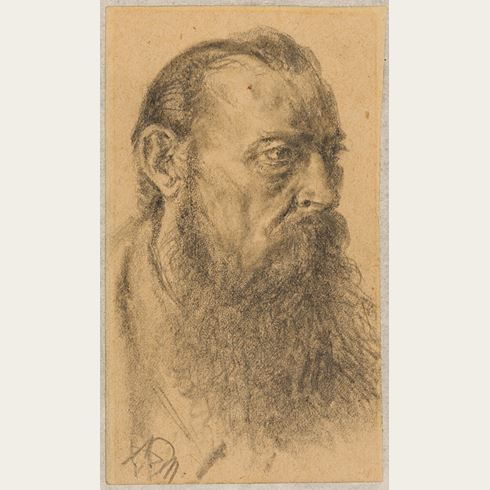

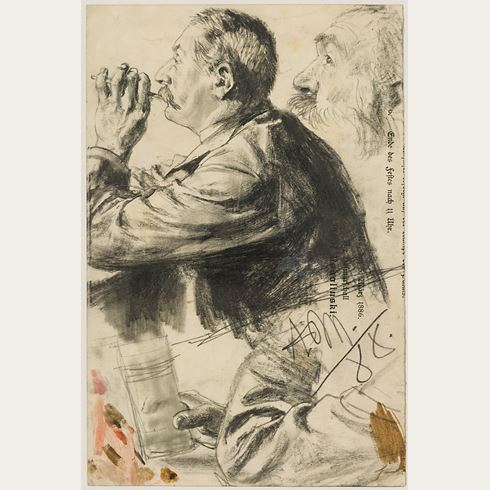

The Head of a Bearded Man

Signed and dated Ad. Menzel 28 Nov. / 61 at the upper right.

434 x 314 mm. (17 1/8 x 12 3/8 in.)

This powerful gouache study was among the works retained by the artist’s sister, Emilie Krigar-Menzel, when she sold the bulk of the contents of her brother’s studio to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1906. It later belonged to the German-Jewish industrialist and art collector, Adolf Bensinger (1866-1939) of Mannheim, whose collection was mainly formed in the 1910s and 1920s. Apart from the present sheet and a pencil drawing by Menzel, Bensinger owned works by Rosa Bonheur, Alexandre Calame, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Honoré Daumier, Ferdinand Hodler, Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Max Liebermann, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Giovanni Segantini, Hans Thoma and Vincent Van Gogh. The collection was sold at auction in 1940, the year after Bensinger’s death, and the present sheet was one of six lots bought back at the sale, for a total of 45,600 Reichsmarks, on behalf of two of the collector’s intended heirs, his young grandnieces Irmgard and Gabriele Conzen. In 1942, however, the assets of the Conzen family were given to the Nazi High Command in exchange for exit visas to Switzerland, where the family settled that year, and it was not until 1962 that title to the property was eventually returned to the Conzen heirs.

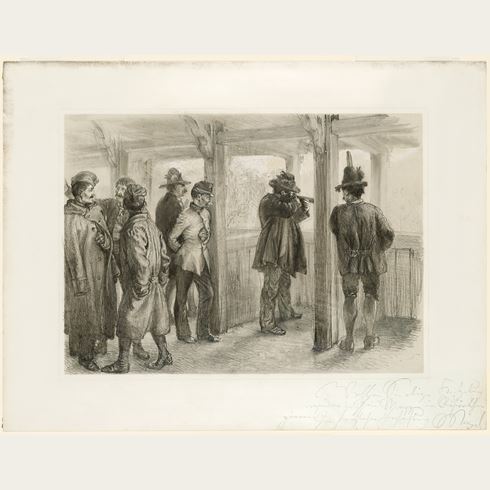

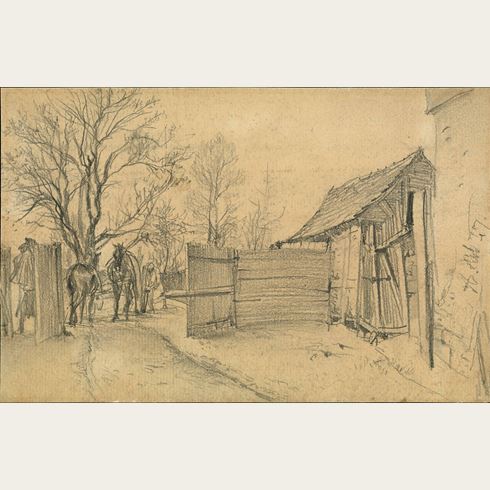

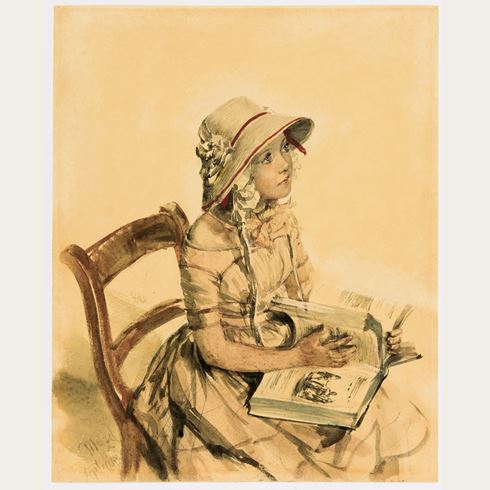

Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel began his career working in his father’s lithography shop in Breslau (now Wroclaw in Poland) and later in Berlin, where his family moved in 1830. A brief period of study at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1833 seems to have been the sum total of his formal training, and he is thought to have taught himself how to paint. At the outset of his career he worked as an illustrator, his activity in this field perhaps best exemplified by a series of some four hundred designs for wood engravings produced to accompany Franz Kugler’s History of Frederick the Great, published in instalments between 1840 and 1842. During the late 1840’s and 1850’s he was occupied mainly with a cycle of history paintings illustrating the life of Frederick the Great.

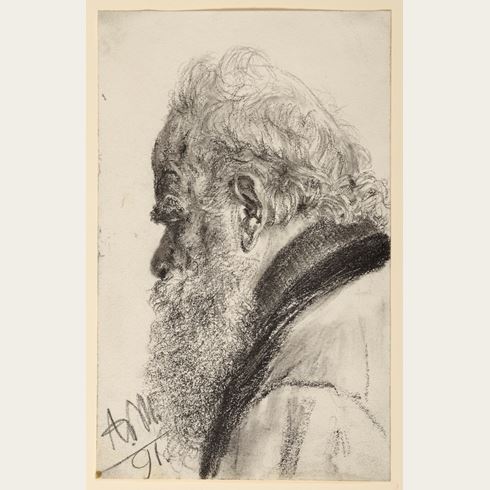

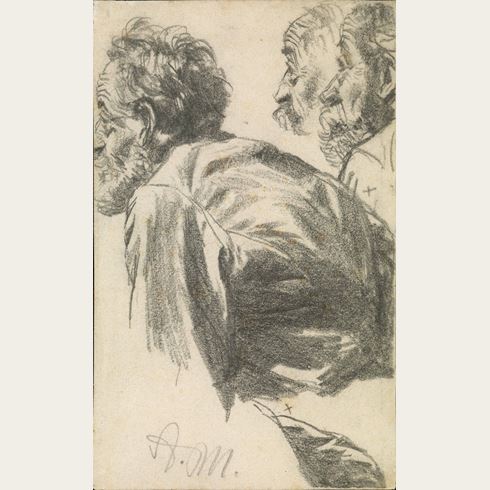

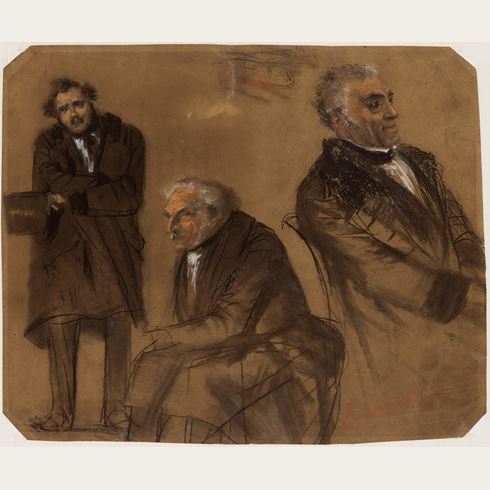

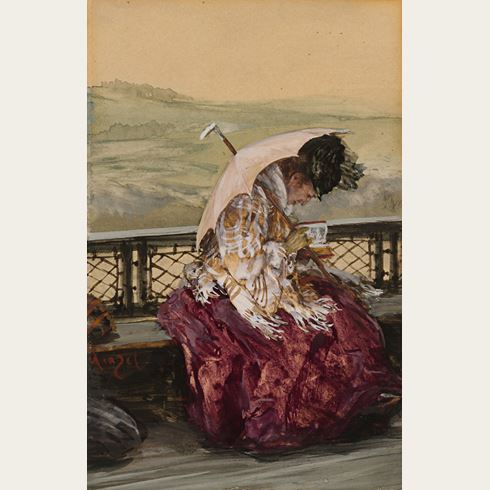

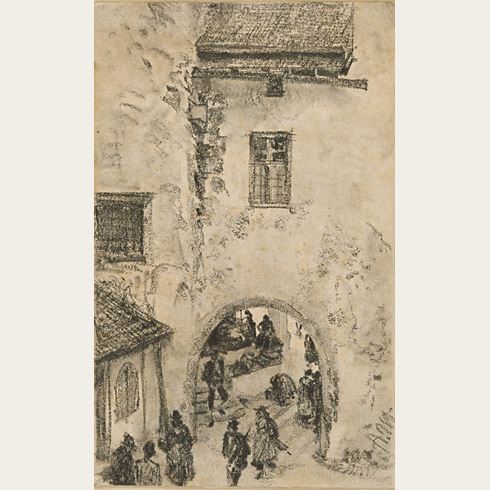

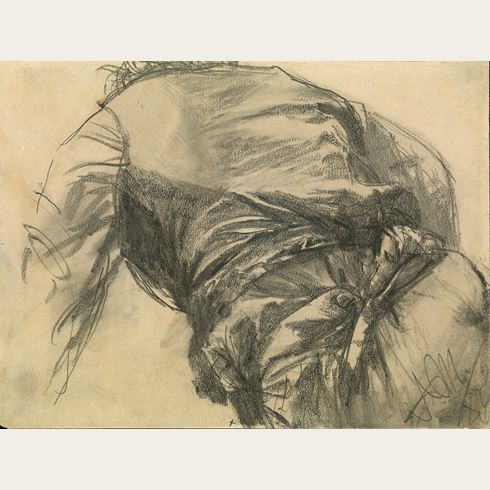

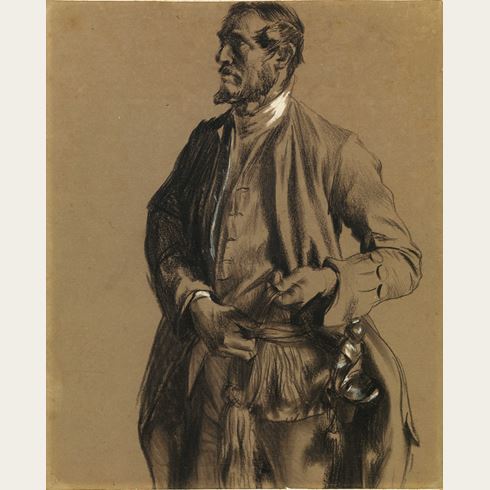

In 1861 Menzel received his most important official commission, a painting of The Coronation of King William I at Königsberg, on which he worked for four years. In the following decade, his lifelong interest in scenes of contemporary life culminated in what is arguably his masterpiece as a painter; the large canvas of The Iron Rolling Mill, painted between 1872 and 1875 and immediately purchased by the National-Galerie in Berlin. The last three decades of his career saw Menzel firmly established as one of the leading artists in Germany, a prominent figure in Prussian society and the recipient of numerous honours including, in 1898, elevation to the nobility. In the late 1880’s he began to abandon painting in oils in favour of gouaches, although old age meant that these in turn were given up around the turn of the century. Yet he never stopped drawing in pencil and chalk, able always to find expression for his keen powers of observation. A retrospective exhibition of Menzel’s work, held at the National-Galerie in Berlin a few weeks after the artist’s death in 1905, included more than 6,400 drawings and almost 300 watercolours, together with 129 paintings and 250 prints.

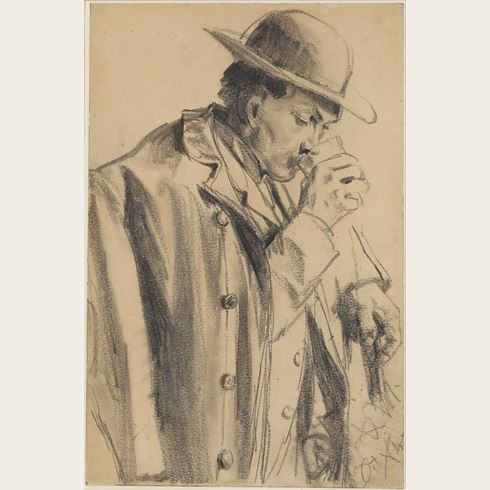

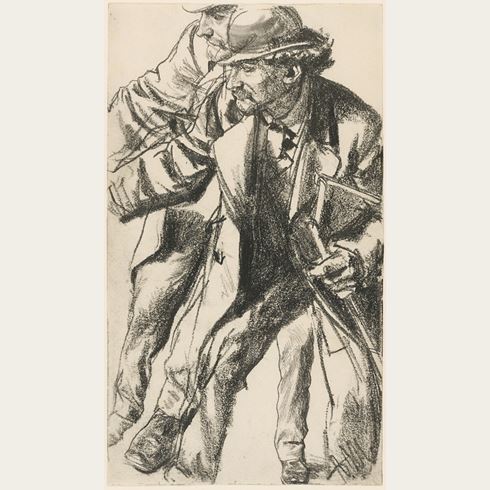

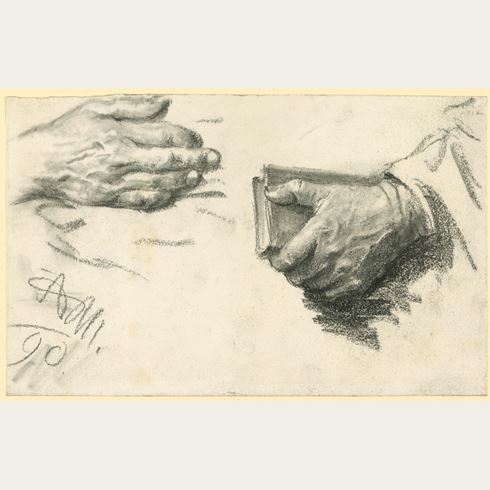

A passionate and supremely gifted draughtsman, Menzel was equally adept at watercolour, pastel, gouache and chalk. He was also able to draw with either hand, although he seems to have favoured his left. An immensely prolific artist (over four thousand drawings by him, together with 77 sketchbooks, are in the collection of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin alone), it is said that Menzel was never without a sketchbook or two in his pocket. His friend Paul Meyerheim described the artist’s appearance: ‘In his overcoat he had eight pockets, which were partially filled with sketchbooks, and he could not comprehend that there are artists who make the smallest outings without having a sketchbook in their pocket…an especially large pocket was installed…to hold a leather case, which held a pad, a coupe of shading stumps and a gum eraser.’ Menzel was widely admired as a draughtsman by his contemporaries, both in Germany and abroad, and Edgar Degas, for one, is known to have owned at least one drawing by him.

Provenance

By descent to the artist’s sister, Emilie Krigar-Menzel, Berlin

Adolf Bensinger, Mannheim

By bequest to four of his great-nieces and nephews

Bensinger sale (‘Nachlass-Verstiegerung der Gemäldesammlung sowie Einrichtung Kommerzienrat Adolf Israel Bensinger’), Mannheim, Fritz Nagel at Werderplatz 12, 22 February 1940, lot 49 (‘Kopf eines bärtigen Mannes nach rechts gewendet. Oel, 43 x 31 cm, bez. Ad. Menzel 28 Nov.61.’, estimated at 10,000 Reichsmarks)

One of six lots bought at the sale by the lawyer Hans Frölich on behalf of Bensinger’s grandnieces, Irmgard and Gabriele Conzen, Berlin-Schlachtensee

Given with the rest of the Conzen family’s assets to the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht in 1942 in exchange for exit visas to Switzerland

Private collection

Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 9 October 1997, lot 51 (bt. Krugier)

Jan Krugier and Marie-Anne Poniatowski, Geneva.

Literature